Journal of a Plague Year

After Ukraine came the most terrifying experience of my life: a lawsuit

The knocking – loud and persistent – pulled me out of a deep sleep. Jarred into full consciousness, my feet were on the floor before my eyes had adjusted to the dark. The noise stopped, leaving only the thumping of blood in my ears. In the darkness, I reached for my pistol in the bedside drawer – more from reflex than conscious thought. Feeling it’s familiar weight in the palm of my hand felt comforting, but at the same time, slightly absurd in the quiet of my room.

I eased open the bedroom door and padded slowly down the hallway hugging the walls to avoid the dappled yellow light from the street. On the other side of the door pane, a shape moved, partially blocking the light. ‘BRRRRRRRRRRRRT… … BRT,’ the doorbell shrieked. Whoever it was, they weren’t going away. I took a deep breath to ease the pounding in my head, exhaled softly and then walked towards the door.

It was 3 July – a national holiday which made my abrupt awakening even more alarming. I had been back from Ukraine for almost three months but couldn’t shake a pervading feeling of uneasiness that kept me constantly on edge, grappling with the specters of my imagination.

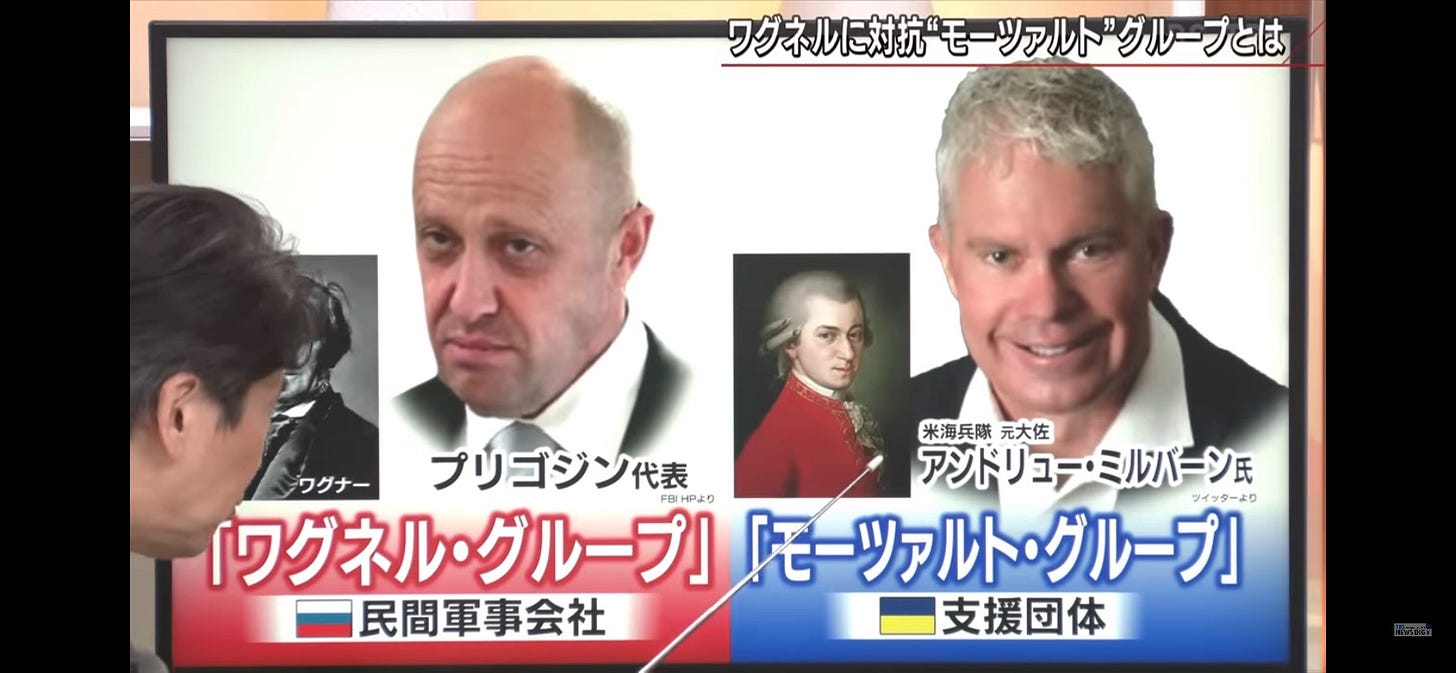

In Ukraine the threat of death from random violence – real enough by itself – became increasingly personal as a pro-Russian campaign of disinformation mispresented me variously as a Ukrainian special forces brigade commander, bitter mercenary and – improbable though it may seem – organ harvester. People started to threaten me online. At the time, working amidst the rubble of Bahkmut, the prospect of being the target of some internet troll didn’t trouble me. But then, enter the Wagner Group -- with Yevgeny Prigozhin leading the pitchfork crowd in pursuit of the Mozart Group. Wagner was operating in our area at the time, often behind Ukrainian lines – which made the threat quite real.

Still, Donbas was a long way from Tampa – I told myself. Then, a month after my return, a Russian TV producer contacted me on WhatsApp to request an interview with his team at my home. I turned him down, of course – but the incident left me unsettled. A few days later, I found myself confronting a misplaced late night pizza delivery man with Glock in hand. My expression alone was enough to send him scurrying back to his car leaving me feeling foolish and relieved.

And now, as I crept towards the door, the dark shape became a woman --– short, plump and bespectacled. A wolf in sheep’s clothing, if there ever was one.

Jamming the pistol in the waistband of my shorts, I turned the handle and pulled the door open.

‘Are you Andrew Milburn?’ the woman asked, in a tone intended perhaps to carry the authority of officialdom, but undermined by a treacherous quaver as she came to the last two syllables of my name.

Without waiting for an answer, she moved as though her life depended on it. The next second, I had a sheaf of documents in my hand, and she was scurrying down my drive towards a waiting car for a quick get-away. What she left in my hands would, in the months to come, frighten me more than any number of death threats.

The documents were a summons to civil action. I knew instantly what it was about.

One Michael Ryan Burke, a former Marine, was accused of raping an American girl in Lviv, Ukraine in the early days of the war. I had written an article about the incident for Task and Purpose and – at the request of the Ukrainian police – had put out word among American volunteers to be on the lookout for Burke, their only suspect.

Burke made it Poland and back to the United States before he could be questioned by Ukrainian or Polish police. He then found a lawyer with a reputation for taking high profile, long-shot cases and was now bringing a lawsuit against Task and Purpose and me for defamation.

As compensation, Burke wanted 25 million dollars by way of ‘special damages, presumed damages, actual damages and punitive damages’. Worst of all, I was now subject to a ticking clock. The summons gave me 20 days in which to respond or face summary judgment. I had to find a lawyer – fast.

This was uncharted territory. None of my previous experience would help me – except perhaps a determination not to allow fear to push me into a settlement. I needed to win – not only to avoid paying an exorbitant sum that I could ill-afford, but to clear my name.

Burke and I had never met – never been closer, to my knowledge, than the several hundred miles that separate Kyiv from Lviv. But I knew and trusted the people who were asking for my help: one was a former Marine with whom I had served, and the other a former Chicago cop who now headed up another volunteer organization operating in Ukraine at the time. The Ukrainian police had also turned to me for help in finding Burke simply because I was American and was there. There was another force at play here too: a sense of responsibility for Burke because we both shared the title Marine. It was a feeling without any legal justification but visceral, nonetheless. Other Marines will perhaps understand.

Getting involved didn’t feel like a decision at the time. And despite all that followed, I never quite reached the point of wishing that I hadn’t. But I came close.

The fact that Burke was a former Marine drove my decision to write the article. Task and Purpose was a military oriented media outlet, and a crime committed in a war zone, allegedly by a former Marine, was grist for the mill. I had spoken with all available witnesses and had most of the story. The editor agreed that it was both substantive and newsworthy. I wrote the article in less than three hours as the occasional Russian shell slammed into the street below my window.

Burke, I learned, had come to Lviv with the intention of volunteering with one of the aid organizations that had sprung up in the city at the start of the war. He was a former Marine reservist who had served as a senior non-commissioned officer with a reconnaissance unit in Iraq. Now he was in Ukraine, ostensibly to help, but perhaps – as my lawyer claimed – ‘without much intention of doing anything much at all.’ He met a girl and invited her on a date after which he allegedly raped her. Then he disappeared -- with various reports putting him in Kyiv and Poland and all points in between. In Kyiv, as I wrote the article, the lights were flickering – electricity was intermittent, and much of the city was dark. It was going to be hard to find him.

And so it proved. Burke escaped across the border to Poland and back to the United States. A few months later, his cause was taken up by the editor of a national on-line media outlet with a reputation for wide-distribution yellow journalism. This editor and I had clashed several weeks previously after he called me with questions about a Marine who was missing in Ukraine. The family had requested my help in finding out what had happened to him. The editor wanted me to comment about the fact that he had been discharged from the Marine Corps under other than honorable conditions. The conversation did not end well. Later, armed with the lawsuit brought by my erstwhile partner at the Mozart Group plus Burke’s complaint, the editor wrote an article that was sharply critical of me, implying that I had ruined Burke’s life with little evidence to support my article.

The editor’s article was duly posted in the Early Bird giving it widespread dissemination throughout the Department of Defense, and even soliciting an inquiry to one of my Mozart colleagues from the Secretary of Defense. It didn’t matter of course that the article avoided burdening the reader with context such as police reports and Burke’s determined efforts to avoid the authorities. The damage to my reputation seemed – at least to me – to be catastrophic.

In this I was mistaken. It is true that some people whom I had thought of previously as friends cut me dead, but they were by far the minority – and now I count myself lucky that they did so. Nevertheless, more than one job offer had evaporated in the wake of the article written about me – and reeling financially from the lawsuit that I had just won, I was not in a good place for this latest blow.

I won the lawsuit against my former partner at the Mozart Group –but it was a mentally taxing and absurdly expensive process that had left me feeling drained.

The summons brought a feeling of isolation and a fear more profound than any I had previously experienced. Now if that sounds off-key, coming from someone who has faced death in combat …… well, it’s absolutely true. The lawsuit threatened every aspect of my life fundamental to my identity. Never mind the First Amendment – I was fighting for my life.

I learned again that lawsuits teach you who your real friends are. No one, it seemed, wanted to be in the casualty radius of this one– to include the 8 defamation attorneys recommended by friends who, without exception, rejected me on first contact. ‘It’s going to be an impossibly complex and expensive case,’ warned one; ‘Do you own a home?’ asked another. I was one week away from summary judgment.

As my increasingly frantic search for representation continued, I tried to remember anything that might help me in my defense against Burke. Slowly, infuriatingly, my memories of that time emerged in fragments rather than a continuous stream.

It was early March 2022, and Kyiv was about to fall. At least, that’s how it seemed at the time. The Russians were hammering the city with artillery and fighting their way into its northern suburbs. The frigid air was heavy with anticipation of the impending onslaught, the tension reflected on the faces of soldiers manning barricades at every streetcorner and the few civilians hurrying along empty sidewalks.

I remember a truck parked outside the ornate opera house on Volodymyrska. Soldiers perched atop wooden crates of weapons handing shiny new AK-47s down to a long line of waiting

civilians. Until the previous week, these people had been students, IT specialists, waiters, and shop-owners with little in common and absolutely no intention of ever wearing uniform.

‘They need help – show them how to use these things, how to fight – just the basics or they have nothing,’ A Ukrainian special operations officer asked me with understated urgency. His request led within a week, to the birth of the Mozart Group, an organization that soon gained a reputation for taking extreme risks in pursuit of our mission.

Sometimes it felt as though we had fallen through the looking glass into a place that was quantumly removed from our previous lives. Burke and I crossed paths just as that was happening. Perhaps in my mind, the stark memories of that year had eclipsed lessor events.

The deadline was on a Monday. On Friday I found a lawyer. Ed was a friend of a friend who worked for a big law firm in Missouri. He had a great reputation, and wanted to help, but wasn’t particularly sanguine about my prospects. Nevertheless, he offered to take on the case just for the preliminary stage which was my reply to summons. It was a start.

‘Write down everything you can remember about the incident,’ he advised me. That weekend I tried to do exactly that, but my memory stubbornly refused to release information about the evidence I gathered against Burke. The notebook I had used at the time was gone – probably still in Kyiv. My Signal application had erased all messages on a pre-set timer – leaving no way of retrieving them.

Self-doubt started to creep in – an unwelcome stranger whose presence grew the more I tried to recall facts. I thought about the effect that my reporting must have had on Burke’s life – the isolation and fear that I knew all too well. My ability to communicate to a mass audience at that particular point in time lent me considerable power. The question was whether I had used this power impulsively with unjust consequences.

I dreaded Ed’s call on Monday. When it came though he wasn’t interested in my weak excuses about memory failure – he had good news:

‘Task and Purpose are fighting this lawsuit. They think he did it.’

Those two sentences flooded me with relief – as welcome as oxygen after a long breath hold. I was no longer alone.

Task and Purposes’ legal team started digging around and uncovered police reports as well as statements from the US Embassy in Poland. That was enough for them to defend the article.

Ed also decided to take my case. My joy at these developments was tempered by the realization that this was going to be a very expensive process. I was covered by T&P’s defamation insurance but at a billing rate that might have covered costs during the era of LA Law but was nowhere close now. Not that I was complaining -- I would take appallingly expensive over ruinous.

The only problem was that Burke had no skin in the game. With his pro-bono representation, he would keep requesting extensions, knowing that it would cost me and not him. Over the course of the following year, I watched his legal team’s machinations whittle down my costly retainer with inexorable intent. It was just like Bleak House.

Confronted with police reports and pictures plus statements from the US Embassy and a swathe of witnesses to include a particularly damaging deposition from a Canadian journalist, the defending team felt confident that Burke would drop the case. Instead, his Burke’s lawyers shifted the focus of their claim from defamation to conspiracy to assault.

Burke claimed that I had sent out Tweets to the Mozart Group exhorting its members to do him harm. My actions had caused Burke ‘extreme and continuous fear, that he will (sic) be assassinated’. My ‘criminal conduct was ‘flagrant and heartless…. utterly intolerable in a civilized community.’ I had apparently led a group of mercenaries in pursuing Burke with clear intention to do serious harm not just to his ‘untarnished’ reputation but to his life -- ‘without,’ it shrilled, ‘a shred of evidence.’

This was a much more serious charge than defamation. I was now alone and – worst of all – uninsured. What followed was a dark and very expensive two months as my legal team rounded up witnesses to demonstrate the absurdity of this claim.

Then at last – 6 months after the initial summons, it finally appeared that Burke’s lawyer was ready to throw in the towel. It had taken several weeks of persuading to get him to this point and Ed was as excited as I had ever heard him.

And then Burke’s lawyer had a stroke, leaving every part of him – aside from his eyelids – paralyzed. I thought that might be the end of it, but Burke found another lawyer – a protégé of the stricken one – who was also willing to work pro-bono, and we were off to the races again.

It was in late June, a full year after the pounding on my door, that the case was dismissed ‘with prejudice’, which means that Burke cannot file again. I came out of it with reputation intact but at such a cost that my victory seemed to me, at first, Pyric.

But I was wrong - it was an absolute bargain. This last year is the only time I remember being awash with self-doubt. The one time when I felt that I was confronting my deepest fears and falling short. Emerging from that with renewed strength eclipses any financial cost. I can recover the money – but never want to return to that part of me that doubted myself.

A few days after the lawsuit was dismissed, I got a call from someone I hadn’t heard from in over a year:

‘Hey man I was rooting for you,’ said my erstwhile friend, ‘Now you can put all this stuff behind you.’

And he’s right – I can.

Well done Andrew. You did it for your Marines, your sister, and the victim.

Andy, this whole story is wild - to hear it on The Team House, and now to read it in even more detail is mind boggling. I’m so sorry that you had to go through this, but glad that you will be stronger for it. I hope you continue to speak the truth. We need more of it.